The Price of Wonder: Inside Indonesia’s Ijen Volcano

Beneath the Mask at Ijen Volcano

There are few places on Earth where fire burns blue. East Java’s Kawah Ijen, a caldera lake perched nearly 2,800 meters above sea level, is one of them—a place where geology, labor, and tourism collide in a surreal theatre of smoke and flame.

Ijen is not simply a volcano; it is a living archive of Indonesia’s industrial past and present. For decades, miners have descended into the crater at dawn, chipping away at hardened sulfur deposits formed by the volcano’s gas vents. The material, bright yellow against the ashen landscape, is carried by hand in baskets that can weigh up to 70 to 90 kilograms, balanced across shoulders worn smooth from decades of repetition. The sulfur feeds industries from sugar refining to cosmetics. For many, it remains the only livelihood available.

The Labor Behind the Beauty

Sulfur mining at Ijen began under Dutch colonial rule in the early twentieth century, and while the world has changed, conditions at the crater remain hauntingly familiar. Miners still work without mechanized tools, breathing in sulfur dioxide that can scar the lungs and corrode teeth. Protective masks are rare luxuries; most use damp cloths tied around their faces. Health insurance, regular medical checks, or governmental safety regulations are largely absent. Some NGOs have stepped in with donations of gas masks and first aid supplies, but comprehensive government intervention has been slow, intermittent, and often symbolic.

The Indonesian government has promoted Ijen as a tourism destination, a national geological wonder, yet the miners who make the landscape so photogenic are rarely the beneficiaries. It is a paradox common in postcolonial economies: the same bodies that endure the harshest conditions become aestheticized in travel brochures.

Science in the Dark

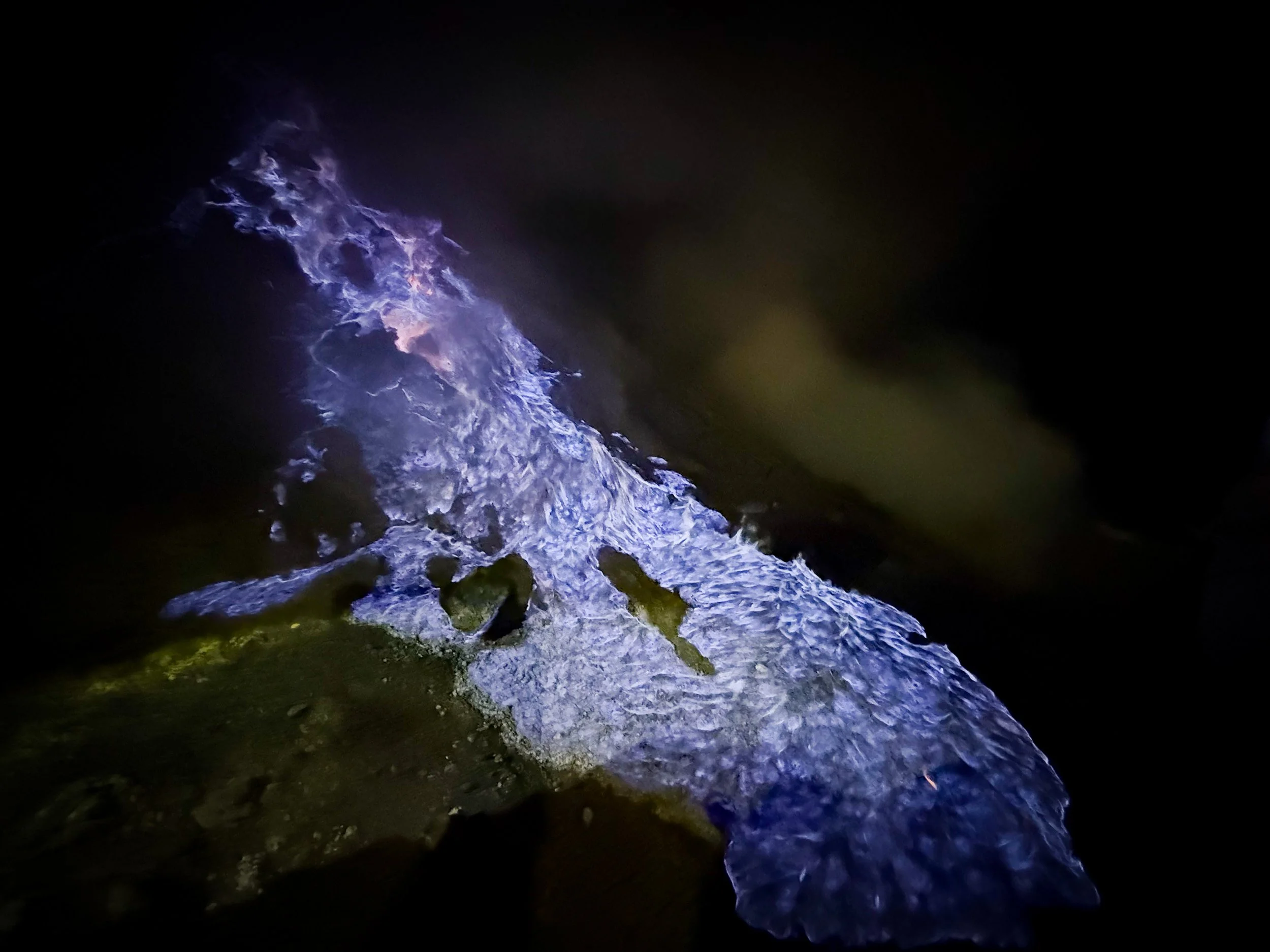

What draws so many travelers here—including me—is the blue fire, an ethereal, electric phenomenon that feels almost supernatural. But in truth, it is chemistry at its most poetic. The flames are not lava, but sulfuric gases that ignite as they emerge from fissures in the earth, burning at temperatures above 600°C (1,112°F). The result is a ghostly glow visible only at night, a rare confluence of heat, pressure, and gas that exists in only two places on Earth: here, and in Iceland.

Seeing it for the first time, I could not decide whether I was witnessing something divine or disturbingly human—nature at its rawest, yet shaped by extraction and spectacle.

The Trek into the Underworld

I left my villa at 10:30 p.m., organized through Sumberkima Hill Retreat in Bali, who coordinated the entire experience. We crossed by ferry to Java, arriving just before midnight, and began the hike by torchlight. The air was thin and cold, and the ascent—three kilometers of incline—felt endless in the dark.

This was my first time wearing a gas mask. The guide handed it to me at the crater rim, warning that without it, I would barely last five minutes below. The moment I put it on, the air felt mechanical, filtered, forced, and suddenly the reality hit: I was about to walk into a cloud of toxic gas, voluntarily.

Descending into the crater was chaos, a cluster of headlamps, camera flashes, and hikers pushing to catch a glimpse of the blue fire before dawn. At one point, the crowd bottlenecked, and I stood surrounded by sulfur smoke so thick it erased the horizon. I could feel my heart racing beneath the hiss of gas filters. It was claustrophobic and thrilling, a dance between awe and fear.

Yet when I finally reached the base, all sound fell away. The flames rippled across the rock like liquid electricity. I stood there for several minutes, not as a tourist, but as an anthropologist in awe of humanity’s strange relationship with danger and beauty.

We risk everything for wonder. And we commodify it just the same.

Reflections at the Crater Rim

By the time I returned to my villa at 11:30 a.m., my clothes reeked of sulfur and my legs trembled from exhaustion. I slept the entire afternoon, still tasting metal in the back of my throat. And yet, I would do it again.

There is something about Ijen that refuses to let you leave untouched—a place where you witness, in one night, the full spectrum of human endurance, exploitation, and awe. The miners, the tourists, the flames—all become part of the same ecology of survival and spectacle.

Anthropology teaches us that meaning lives in contradiction, and Ijen is exactly that: sacred and industrial, brutal and breathtaking, ancient and ongoing.

Apple Mountain

Bonus Story: Why It’s Called “Tomato Mountain”

In the video below, my guide — whose family has worked as sulfur miners for generations — explains the story behind Tomato Mountain, the smaller peak beside Ijen.

Travel Notes

Booking: I arranged my trek through Sumberkima Hill Retreat, who coordinated transport and guide services to Java.

Timing: Depart around 10:30 p.m.—the blue fire is only visible in darkness.

Safety: A gas mask is essential; without it, the sulfur dioxide is dangerous. Hiking shoes are non-negotiable. You will also need a medical clearance before trekking.

Physical Demand: It is a strenuous climb, not for the faint of heart, but the experience is unforgettable.

Sampai jumpa laggi!

Ijen left a trace on me that no photograph could hold — the scent of sulfur, the hum of human will, the beauty stitched with burden.

It is in these contradictions that the Archive continues to grow.

Until next time,

Shan

Sources and Further Reading

BBC News. (2019). The men who mine the ‘Devil’s gold’. https://www.bbc.com/news

National Geographic. (2015). The Struggle and Strain of Mining “Devil’s Gold”. https://www.nationalgeographic.com

Smithsonian Institution, Global Volcanism Program. Ijen Volcano Profile.

Reuters. (2019). Indonesia’s sulfur miners risk their lives for pennies.

Gunawan, H., Caudron, C., Pallister, J., Primulyana, S., Christenson, B., Mccausland, W., van Hinsberg, V., Lewicki, J., Rouwet, D., Kelly, P., Kern, C., Werner, C., Johnson, J. B., Utami, S. B., Syahbana, D. K., Saing, U., Suparjan, Purwanto, B. H., Sealing, C., … Hendrasto, M. (2016). New insights into Kawah Ijen’s volcanic system from the Wet Volcano Workshop Experiment. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 437(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1144/sp437.7